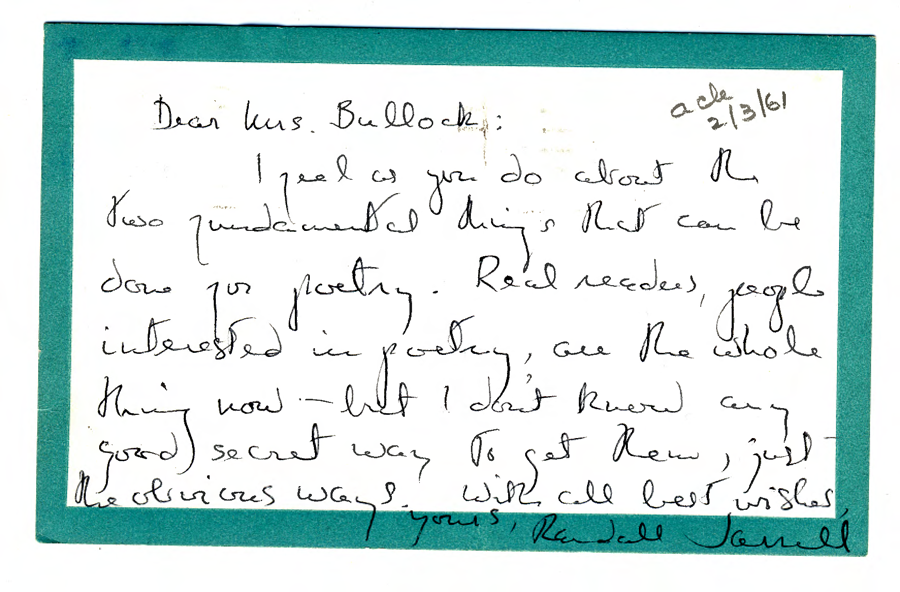

Dear Mrs. Bullock:

I feel as you do about the two fundamental things that can be done for poetry. Real readers, people interested in poetry, are the whole thing now—but I don’t know any good secret way to get them, just the obvious ways.

With all best wishes.

Yours,

Randall Jarrell

In this 1961 postcard from our archive, Randall Jarrell corresponds with Academy of American Poets Founder Marie Bullock about the importance of getting new readers interested in poetry. Jarrell, who was elected to the Board of Chancellors in 1956 and would hold the post until his death, was likely responding to a call to the Chancellors for their advice in what could be “done for poetry” in America in 1961. Though Jarrell was highly regarded as a poet, literary essayist, and poetry critic, he was not the only renowned poet Bullock may have reached out to on the Board of Chancellors during his tenure; Jarrell’s Chancellorship coincided at various points with that of W. H. Auden, Louise Bogan, Robert Lowell, Marianne Moore, and Richard Wilbur, among many others.

At the time he had written this postcard, Jarrell had just recently published his fifth collection, The Woman at the Washington Zoo (Atheneum, 1960). Jarrell, who thought of the poet as “a sort of accident-prone worker to whom poems happen,” was inconsistent in his output, the lulls of which were the cause of some of his depressive episodes. For a nine-year period, from 1942 to 1951, Jarrell wrote steadily, and published four collections in that time. But it would be nine more years until he had enough poems to collect in The Woman at the Washington Zoo, more than a third of which consisted of translations. However, his efforts proved worthwhile, as The Woman at the Washington Zoo was awarded the 1961 National Book Award, beating out works by finalists Auden, J. V. Cunningham, Robert Duncan, Donald Justice, Howard Nemerov, Anne Sexton, and Yvor Winters, among others.

Here Jarrell talks about the essential role readers of poetry—not just cursory readers, but what he calls “real readers”—play in the art form, and how he’s unsure of how to get more of these readers. Jarrell was, without a doubt, one such “real reader,” whose love of literature was unbridled. In libraries, he once said, he felt “soothed and calm and secure,” like “a baby come back to the womb.” And when asked or compelled to provide a friend, acquaintance, or a student with reading recommendations, he happily provided several suggestions of books worth reading. In a letter, he once wrote, “Telling things to read is something I can hardly make myself finish.”

But a month after writing this postcard, when he was presenting his National Book Award acceptance speech, he took a slightly different stance, saying that poetry is not so easily recommended; in fact, poetry recommendations aren’t necessary at all:

It is customary for poets, in conclusion, to recommend poetry to you, and to beg you to read it as much as you ought instead of as little as you do. The poet says this because of the time he lives in—"a time," writes Douglas Bush, "in which most people assume that, as an eminent social scientist once said to me, 'Poetry is on the way out.'" Now poetry—if by poetry we mean what Frost and Dostoevsky and Freud and Ingmar Bergman share—isn't on the way out, unless humanity is on the way out; when poetry "goes out of a place it is not the first to go, nor the second or third to go, / It waits for all the rest to go, it is the last." Poetry doesn't need poets' recommendations.

While the nature of the exchange between Jarrell and Bullock was regarding the “fundamental things that can be done for poetry,” Jarrell himself did not seem worried about the state of poetry. Jarrell called poetry an all-encompassing obsession, one that lives in the blood, “an old drug like love or dreams” that will not die out. At the end of his speech, Jarrell said, “Poetry, art—these too are occupations of a sort; and I do not recommend them to you any more then I recommend to you that tonight, you go home to bed, and go to sleep, and dream.”